When most people think of the beautiful Scott and Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, they tend to think of the Jazz Age. That is the epithet coined by Scott to explain the wild ride of the 1920s – the drinking, the music, the partying, the real estate and stock market boom. And let’s not forget literary genius.

Just as spiritualism arises after drastic wars, so does wild spending and a lust for life spring up among the survivors. This was especially true after the First World War. And no other couple in America exemplified this hyper-enthusiasm than the Fitzgeralds. Although Scott and Zelda came from very well-established citizens of America with deep roots in the British Isles, Italy and Ireland, both sides of their family showed hints of medieval and Renaissance jazz age rebellion with an occasional side order of sedition.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was the son of Edward Fitzgerald, a native of Maryland, whose family emigrated from Ireland in the 18th Century. Edward’s father, Michael, had married into the distinguished Baltimore Scott family that produced Francis Scott Key, the author of “The Star Spangled Banner.” On the down side, he was also related to the American spy Mary Surratt who would be the first woman publicly hanged by the Federal government for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of President Lincoln. Maryland is a mid-Atlantic state (where Mrs. Surratt lived and owned a tavern as Booth, himself, was a resident) but wildly divided between northern and southern sympathies during the Civil War. Not surprisingly, while Scott was very forthcoming on his relative Francis Scott Key he was virtually silent on his errant female relative.

The surname Fitzgerald has a complicated history. Apparently, “Fitz” is the Norman-French (or Anglo-French) word for “son” and “gerald” may mean “spear rule.” The word “Fitz” is a derivation of the French word for son, fils. In other genealogical studies, it may also derive from Tuscany – in particular, the medieval family Ghiraldini known for its fighting spirit, rebelliousness and chronic cause of aggravation to the elegant Florentines. “Spear rule,” indeed! Today, the Ghiraldinis are mostly associated with a branch of the clan called del Giocondo. Francesco del Giocondo commissioned a portrait of his wife and in true Ghiraldini tradition, she is still aggravating people with her enigmatic smile. Those who admire Leonardo Da Vinci also know the painting was “never finished” and was never delivered to the family. Leonardo travelled with it always and left it to Salai, his bad-boy apprentice who he tolerated despite his “lies, thievery and gluttony.” There is no evidence of the family’s response to this but it couldn’t have been pleasant.

One doesn’t know if Scott Fitzgerald ever knew of his vague connection to Mona Lisa but one suspects he didn’t because he certainly would have mentioned it in a letter or remark. Interestingly, it has been a study of discussion at Oxford’s Trinity College.

In medieval Ireland, a section of the clan was known as the Geraldines and appear first in Munster. By the 16th century, they were up to their usual tricks and several of them were escorted to the Tower of London where they met the typical fate visited upon the enemies of the Tudor gang. In 1534, Thomas Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare, renounced his loyalty to Henry VIII thus leading to the Kildare Rebellion. Thomas’s plan was deeply flawed despite his numerous mercenaries known as The Gallowglass. These were elite soldiers who came gussied up in silk uniforms and fringed helmets. Despite the attractive uniforms and nasty weaponry, the rebellion barely got off the ground. Happily though, there was much Fitzgerald drama in the halls of power in both England and Ireland. Patriotic poems were exclaimed, swords of state were abused, and by February, 1537, “Silken Thomas” was on Tyburn Hill getting the usual Henry VIII treatment. The relationship between Ireland and England which had been so much warmer when Richard III and the Yorkists were running things had descended into the usual barbarism and authoritarianism under Tudorism.

Is it any wonder that F. Scott Fitzgerald himself was a bit of a renegade?

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald’s family also traced some of their ancestors’ history to Maryland. Her mother’s family, the Cresaps and Machens arrived in America during the 17th century. Thomas Cresap, born in Yorkshire in 1694, arrived in the New World where he settled on the Susquehanna River and was deeded over 500 acres of land by Lord Baltimore, Cecil Calvert. He was appointed surveyor and magistrate as well as captain of the militia. Rumored to be a secret agent of Lord Baltimore, he quickly earned the nickname “The Maryland Monster.” Aside from being called “obnoxious,” the details of his apparent monstrousness is unknown. He was eventually jailed and while taken in chains to the courthouse, was subjected to much abuse by the locals. He and his family would eventually flee into the Cumberlands which included parts of Kentucky. Minerva Machen Sayre, Zelda’s pretty mother, would become known as “The Wild Lily of the Cumberland.” She, too, had her rebellion. Unbeknownst to her father, she took off to Philadelphia to join the Drew-Barrymore stock company as an actress. Willis B. Machen shouldn’t have been surprised or outraged; a rebel himself, he somehow managed to serve for five years in the Confederate Government as well as being elected an United States Senator. Quite a feat.

The Sayre side of Zelda’s family is somewhat obscure. The name Sayre is of Welsh origin meaning “wood worker.” But we have no idea if the Sayres emigrated to America from either Wales, Scotland or England. The Sayres landed in New England probably during the early 17th century. They became faithful Yankees, fighting during the Revolutionary War and establishing themselves as successful merchants and farmers. By 1819, the Sayres had arrived in the new state of Alabama and settled in the small city of Montgomery which would become the state capitol in 1846. The Sayres were newspaper editors and lawyers and one, Zelda’s father, Judge Anthony Sayre, served on the Alabama Supreme Court for 25 years. They were pillars of the community and, indeed today, there is still a Sayre Street in the downtown area named after the family.

Unlike the Fitzgeralds, Machens and Cresaps, the Sayres were a more sedate people. But that gave their beautiful and brilliant 20th century daughter, Zelda, something to rebel against. And rebel she did. She was the first “flapper” with bobbed hair, short skirts and a shocking flesh-colored bathing suit. It was also not beyond her to take a snort of illegal corn liquor. But with her husband’s encouragement, she would go on to be a fine writer, dancer and painter. The New York Times recently reviewed the gouache watercolor paintings of her “paper dolls” and called her a genius. And so she was.

Many thanks to Dr. Alaina Doten, Executive Director of the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Montgomery for sharing the genealogical papers of the Sayres, Sally Cline’s biography “Zelda Fitzgerald Her Voice in Paradise,” Henry Dan Piper’s “F. Scott Fitzgerald A Critical Portrait,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby ” and Eleanor Lanahan’s “The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald.”

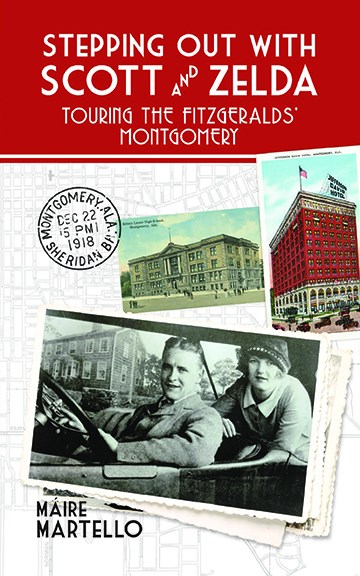

Maire Martello is the author of “Stepping out with Scott and Zelda: Touring the Fitzgeralds’ Montgomery” published by New South Books/University of Georgia Press and is available on Amazon. She is also a frequent blogger at The Murrey and Blue.

1 comment