“Let us consider some of our genuine English culinary assets. Among the best of them are our cured and salted meats. Hams, gammons, salt silversides…”

So begins one of Elizabeth David’s chapters in “Spices, Salts and Aromatics in The English Kitchen,” a charming book that takes us through centuries of English cookery with its yin and yang of salty and sweet, pungently bitter and honeyed agreeableness. Her book is a lesson to those of us in the Americas and Europe who so disdain English food based on a bad meal in a chain restaurant or a hastily grabbed sandwich at Tesco Express. David illuminates a vision of past glories and shows a way forward by trusting to an old cuisine based on freshness, seasonality and creativity. With that in mind, here are some recipes that reach far back in time and yet are still appropriate on a modern table at the holidays:

Spiced Beef

While not quite medieval if The Forme of Cury (The Method of Cooking) is anything to go by, Spiced Beef has been a British and Irish Christmas season favorite since the Elizabethan era. Given the luxurious amount of sweet and spicy elements that goes into the dish, and the availability of beef, it is hard to believe that it was completely unknown to someone of King Richard the III’s lifetime or status. In any case, it is a delicious and interesting dish both for its unique flavor and unusual preserving technique that so intrigues the amateur chef: the weighing down of a hunk of beef with a heavy plank and two large cans of refried beans.

According to Elizabeth David, this dish is particularly popular in the counties of Yorkshire, Cumberland and Sussex. “The Harrods Book of Traditional English Cookery” claims it as a specialty of Leicestershire and since a very popular version of it was (and may still be) sold in its grand food halls, who are we to argue? In New York City, of course, it is known as pastrami and sold, hand cut and served on rye, at the popular Katz’s Deli on the Lower East Side. The word “pastrami” comes from the Turkish word “bastirma” meaning “pressed meat.” In Pakistan, it is known as “Hunter’s Beef” which returns us to the thought of when this dish popped up in the West. Could it or its preserving technique been brought back from the Middle East by the Crusaders? It is certainly hard to believe that the Tudors had anything to teach us that wasn’t first known to generations of the Byzantine wars.

Here’s how to do it: purchase four to six lbs of Silverside or the American cut called Bottom Round. (Brisket is often used but it is very expensive and once cooked tends to shred like disintegrating rope.) Rub it all over with soft brown sugar and place it in sterilized Tupperware and store in the crisper section of the refrigerator. Do the same thing the next day – you will see that water is drawn from the beef but that is how it should be. On the third day, rub the meat with a substantial mix of crushed kosher or sea salt, juniper berries, allspice berries, black peppercorns, a pinch of clove and half a teaspoon of Prague Powder. (Prague Powder will preserve the pink color of the meat and is available on Amazon. It is optional.) Continue to rub and turn the meat for the next 8-10 days. Always return to the crisper or coldest part of the fridge. After a few days, you will notice a very inviting smell.

On Day 8-10, take the roast out of the fridge and wipe clean. Place in a tight-fitting dutch oven and pour in a cup or two of water so that it comes up half way up the roast. Set the oven temperature between 250-290F/143C. The water must simmer, never boil. Roast it between 3-5 hours or until it registers 165F/74C on a meat thermometer. Once cooked, let it cool in the pot and then wrap it in wax paper or tin foil. Weigh it down with a cutting board and two large cans and place it overnight at the back of the fridge. When ready to eat, bring it to room temperature and slice very thin. Serve it with brown or rye bread and strong mustard or horseradish and some pickled vegetables or cole slaw. It would be perfect the day after Christmas served as part of a cold collation. As the week goes by, it will only improve in flavor. Elizabeth David notes, “the beef will carve thinly and evenly, and has a rich, mellow, spicy flavor which does seem to convey to us some sort of idea of the food eaten by our forebears.”

Salat. XX.III.XVI

Take persel, sawge, garlect, chibolles, oynouns, leek, borage, myntes, porrectes, fell and ton tressis, rew, rosemarye, purslarye, laue and waische hem clene, pike hem, pluk hem small with thine hand and mix hem well with rawe oile, lay on vynegur and salt, and serve it forth.

This is a recipe directly from Richard the Second’s cookbook, The Forme of Cury. While I would never contradict Clarissa Dickson Wright who has said that medieval salads were generally a vegetable mix and not greens, this clearly has much more in common with modern salads than Miss Dickson Wright would have us believe. To my mind, this salad is definitely overkill but then again King Richard II was a kind of overkill guy.

Elizabeth David, in her cranky book “Christmas,” suggests salad as an appetizer but in European fashion, might well be served after the main course along with some nice cheese. In her book “Jane Grigson’s Vegetable Book,” Mrs. Grigson has an interesting chicory salad that she serves at Christmas. Served with apples in a mayonnaise dressing, it suspiciously reminds one of a 20th century invention, the Waldorf Salad.

Chicory is a bitter green with a complicated history. Medieval monks in Europe grew it but probably only used the tender leaves and blue flowers of the plant. The most common form of it today, also known as endive to both the Americans and the French, is the forced white or yellowish chicon (bud/root) cultivated by the Belgians in the 1840s. To the Italians, dressed in its pretty, ruffled red clothes, chicory is known as radicchio or treviso and is ludicrously expensive. Because of its bitterness, it has been used as a coffee substitute seemingly throughout the world during hard times. New Orleanians have made the coffee/chicory combination a classic at Cafe Du Monde in the French Quarter along with the famed “beignets”. Medieval people would have simply strewn their “salats” with this precious herb.

Mrs. Grigson’s Christmas Salad:

Mix equal quantities of diced cold poultry or game bird and diced, unpeeled eating apples and sliced chicory. Dress with vinaigrette alone for guinea fowl or pheasant. Mayonnaise can be added for light poultry, together with some cubed Gruyere cheese. An alternative dish using chicory is to cook it in cream and butter as the French do with the summer herb, savory.

My Simple but Delicious Salad Fit for a Medieval King:

Mix crisp lettuce along with baby spinach, arugula (rocket) or watercress or any herb on hand. Make a dressing of 1/4 cup of virgin olive oil, a splash of good vinegar, a dash of Dijon mustard and salt and pepper. Mix well and dress salad at the last possible moment before serving. If you must, you may add some red onion or sweet pepper or herbed croutons.

Queen Elizabeth I Apples

I found this odd recipe while perusing Alice B. Toklas’s classic cookbook which is infamous for the recipe of hashish cakes she naively included in her chapter called “Recipes from Friends.” The rock-ribbed Republican and Catholic convert was chagrined to find that she had been transformed into an early hippie (or belated beatnik) and drug eater.

This simple receipt, however, was submitted by the English painter and baronet, Sir Francis Rose, and suggests an early English pickling method. Again, we see the Tudors being given credit for a dish that is not only easy to make but contains ingredients that were well known to medieval cooks years before Henry VIII was a gleam in his father’s eye. It should be started several months before the holiday season when apples are just starting to ripen and fall from the trees:

“Cook in sugar water whole unpeeled very fine apples until transparent. Then put the apples into jars filled with hot vinegar that has been boiled with honey, allspice and fresh rosemary. Place into hermetically sealed jars (sterilized) and the apples not served for several months.” This would make a very nice addition to a ham or pork dish served at Christmas as they do in the southern United States.

Mince Pye

This evergreen-favorite is also associated with the Elizabethans but came into its own with the Victorians. I suspect mincemeat is much older than the Tudor era because so many medieval receipts for pottage or “tartlettes” mix pork and mutton with honey, lemon and oranges, spices such as saffron and cinnamon, almonds and dried fruit. Again, it demonstrates a sophisticated palate in its use of salty, sweet and acidic developed once the spice trade routes were established. Elizabeth David traces both plum pudding and mincemeat to the Mediterranean. As examples, she cites a fruity Greek pudding with the unappetizing name of “strepte” and an ancient Breton dish called “le far” that resembles a plum and raisin-filled clafouti. Of course, as time passed, the meat disappeared from mince pie and became much more sweet and one-dimensional.

As an experiment, I made two batches of the pies – one using beef suet (from Atora) and one using the truly medieval ingredient of marzipan (marchpane). I was reluctant to use the suet because my husband is still recovering from a beef suet Spotted Dick served at Rules in London. It gave new meaning to the term “stick to the ribs.” Still, I was invested in my menu and could not be stopped.

Serve these mini-pies between Christmas Day and Twelfth Night to ensure good luck:

Mincemeat:

Add a good handful each of currents, raisins, yellow raisins (sultanas), dried cranberries (optional), brown sugar, salt, apple cider vinegar, lemon/orange candied peel*, grated lemon zest and two grated apples to a saucepan. Sprinkle two tablespoons of mixed spice (pumpkin pie spice) over it and stir. Cover with cider or unsweetened apple juice and bring to a boil. Lower heat, cover and cook it down until fruit is soft and sludgy. The salt and vinegar is unconventional but I prefer the chutney-like flavors which cut through all the sweetness. Add a couple of tablespoons of brandy and spoon into sterilized jars. Allow to cool. These can now be stored in a dark, cool place until ready for use.

Pastry:

1 and 1/2 cups of flour, 1 stick/113 g diced cold unsalted butter, 1 t salt, 1/4 cup of cold water

In a food processor, pulse flour and salt. Add butter and pulse until well-combined. Add enough water until the dough comes together and tip out onto a well-chilled, floured board. Bring it together until it forms a ball and refrigerate for at least one hour or overnight. When ready to make the pies, roll it thin and cut circles that will fit small tart pans. Place about a tablespoon of mincemeat, depending on the size of your tart pans, and the grated suet or marzipan and cover with a top crust. Set the oven at 400F/200C degrees and bake for approximately 20 minutes.

The freshness, bright flavor and lightness of these tarts bear no comparison to any store bought variety I have known. The little pies using beef suet added a pleasing umami sensation – the “mouth feel” so prized by tv chefs and culinary instructors but can easily be omitted. Just be sure not to use the nasty mixed peel that appears in supermarkets during the holiday season. Amazon sells very good lemon and orange peel for minimum cost as well as crystallized ginger which would be a nice warm addition.

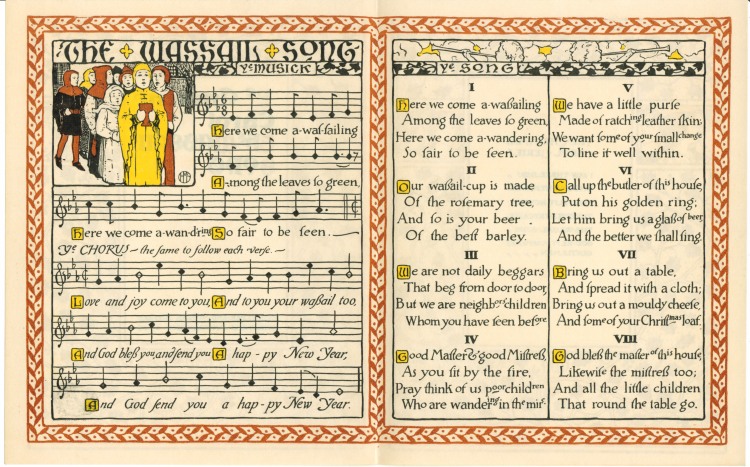

No tasting menu for Christmas can exclude the ever-popular wassail and/or mulled wine that was once known as Lamb’s Wool when served during the harvest celebration of Lammas Day. It is seemingly everywhere these days and even the tackiest grocery store or bodega knocks out a bag of tired spices for the holidays. I picked up my assorted fresh spices at the gift shop at Valley Forge National Park in Pennsylvania and it certainly seems like something both the British and American armies would have enjoyed when heading into winter quarters. Originally, mead was used in the preparation and then hard cider, generally using fermented apples or other fruits, honey and spices such as ginger and cinnamon and whole cloves. Now, more often than not, white or red wine is used. I prepared it with a red wine “blend” following a easy recipe from the superb book “Fabulous Feasts Medieval Cookery and Ceremony” by Madeleine Pelner Cosman. Interestingly, her menu offers mulled wine to be served directly after the starter which implies that it would work very well as an aperitif.

Simply pour the spices into a gallon of excellent wine or hard cider, add half a cup of sugar or honey, two quartered oranges and one lemon. Bring it to a boil and then simmer for an hour or two. Miss Cosman suggests a pinch of pepper or basil for a hit of sharpness. Serve in mugs with a stick of cinnamon. The result is a warming, spicy beverage perfect for a cold night before the wood fire.

You now have a starter, an entree, a side, a dessert and a beverage for your Christmas celebration. Choosing to make one of them will bring you closer to understanding our medieval forefathers and their superb culture and enticing and exotic foods. And God bless you and send you a happy New Year!

It must be coming up to lunchtime – after reading this, I’m suddenly quite ravenous!!!

LikeLike