In all my travels to England, I had yet to visit Fotheringhay, the place where Richard III was born on October 2, 1452, and where his grand-uncle, father, mother and brother Edmund are buried. So, when planning our latest trip this past October, I made it a high priority that my husband and I should visit this important Yorkist site; my main goal was to set eyes on the carved Boar that dates from Richard III’s lifetime. My interest in the boar was because Richard had adopted the white (or silver) boar as his personal badge while he was a young teenaged (or preteen) duke of Gloucester. It is located within St. Mary and All Saints church, only a few hundred yards from the castle remains. Much to my surprise, many visitors overlook the carved boar because it is not easy to locate, and it is not even mentioned in the church’s guidebook.

We were traveling by car from Leicester to Bury St. Edmunds, and Fotheringhay was an easy detour along our route towards East Anglia. It was our first foray into Northamptonshire, and we were excited to be visiting the place where not only the Yorkists had a major family home, but also the place where the Woodvilles had their home base. We were planning visits to other places historically significant to the Wars of the Roses: Ely Cathedral; Croyland Abbey; Cambridge; and Bury St. Edmund. But, for me, the boar was the paramount thing.

Many writers have described the pleasant perspective that greets the eye when approaching Fotheringhay, and they were not wrong. The church is situated in a very large field, at the top of a hill. From miles away, one can see the octagonal lantern at the top of its tower, and can catch a glint of gold from the falcon-in-a-fetterlock flagpole.

The fetterlock-and-falcon symbol was adopted by Edward III’s fifth son, Edmund of Langley, first Duke of York, and became perhaps one of the more predominant cognizances of the house of York, even to the point that Langley used it for the groundplan for his renovation of Fotheringhay Castle.

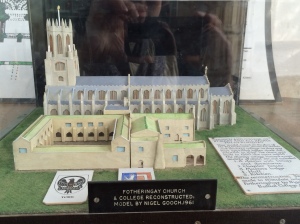

It was Langley who projected a college at Fotheringhay, and it is believed he built a “large and magnificent” choir adjoining the ancient parish church in the town that huddled close to the castle, near the River Nene. Langley’s son, Edward of Norwich, second Duke of York, obtained a charter in 1412 for its endowment, to include a master, 8 clerks, and 13 choristers. In 1415, the duke obtained a royal license to enlarge the foundation, but did not live to see it built. It was his nephew, Richard, third Duke of York, who carried his uncle’s designs into execution and on the 24th of September, 1435, he signed by commission a contract with William Horwood, freemason of Fotheringhay, for the rebuilding on a scale and in a style exactly corresponding to those of the choir erected by Langley.

Edward IV carried on his father’s interest in the church, and gave it new windows of stained glass to the cloisters, along with the windows in the college which were ornamented with shields of arms. He also gave it a new charter, 300 acres of land, and various privileges and liberties, amongst many grants of income from estates and lands in surrounding communities. The goal was straightforward: it was to be a Yorkist shrine of a grand scale and suitable for the remains of his father and brother Edmund when they were reinterred here in July of 1476.

The lavish scale of the shrine is exemplified by the design of the hearse delivered to Fotheringhay to anticipate the final resting place of the Duke of York and the Earl of Rutland. It was originally designed in 1463. “The hearse and its many pennons and banners were mainly the work of John Stratford, the king’s painter. He made the ‘majesty cloth’ of Christ sitting in judgment on the rainbow, a symbolic scene which was to hang over the effigy [of the duke] before the ‘eyes’ of the dead man.” [Sutton/Visser-Fuchs] The hearse was decorated with 51 gilded wax images of kings and 420 gilded wax images of angels. As if that were not grand enough, the hearse was “dusted” with painted silver roses, over which a gilded single great sun, Edward IV’s personal badge, dominated.

The church at Fotheringhay must never have seen a grander day than that of 29 July 1476. This is when an enormous procession led by the king’s youngest brother, Richard, duke of Gloucester, arrived with the funeral cortege. It must have been quite a colorful sight, as a multitude of banners were carried, many depicting religious subjects, such as the Trinity, Our Lady, St. George, St. Edmund and St. Edward – the saints revered by the house of York. Also depicted were heraldic symbols of importance to York: the white hart, the white lion, the falcon-in-fetterlock, and the white rose.

Behind Richard, who was chief mourner, came several distinguished magnates: Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland; Thomas, Lord Stanley; Richard Hastings, Lord Welles; Ralph, Lord Greystoke; Humphrey, Lord Dacre; and John Blount, Lord Mountjoy. The bodies of the dead were accompanied by 3 kings of arms (March, Norroy, Ireland); 5 heralds (Windsor, Falcon, Chester, Hereford); and 4 pursuivants (Guisnes, Comfort, Ich Dien, Scales). Scores of nobles and their household officers on horseback formed a long cortege, and 400 “poor men” on foot carried torches. According to financial records, tents erected outside the church, could accommodate seating space for 1,500 people. And guests attending could expect to be fed very well by the King’s generosity, as this was an opportunity for him to display his munificence to the subjects of his realm. [Sutton/Visser-Fuchs]

When we entered the church last month, it was with this history in mind. As I walked to the north porch entrance, I imagined the spectacle of all the tents and the hundreds of people being fed. I imagined cups of small ale being raised in honor to the Duke, perhaps people telling stories about his life, and how the surviving children resembled their father in looks or deed.

But my goal was to see the boar. I had read about it in David Baldwin’s text, and he described it as being near or within the pulpit. It’s impossible to miss the pulpit, as it is remarkably colorful and elaborate, when contrasted to the rather plain white walls of the interior:

In 1821, H.K. Bonney, archdeacon, made the following observation about the pulpit during his site survey of Fotheringhay, which was undergoing renovations at the time: “The pulpit is original and in good preservation. It is hexagonal, supported on one pillar, and adored with carved panels inserted in a border of tracery. Above are the remains of the canopy, which probably was surmounted by a high crotcheted pinnacle; but which has, since the reformation, given way to a large sounding board. On examining the canopy, whilst it was under repair, some of the ancient gilding, that covered this part of the pulpit, was discovered.”

According to an 1841 treatise by John Henry Parker, the pulpit was presented by Edward IV “as his arms and supporters are carved upon it”. These were carefully cleaned and restored by Archdeacon Bonney in 1821, “whose zeal in antiquarian researches is deserving of the gratitude of this [the Oxford] Society” he wrote. In 1890, C. A. Markham wrote that the pulpit at Fotheringhay was a good example of a paneled oak pulpit of the Perpendicular style, albeit of a design uncommon in Northamptonshire. Markham asserted the pulpit was “erected soon after the year 1440, when the body of the church was built”.

At first I walked around the pulpit several times, admiring the painted panels, but I did not see any carvings as described by these men. After my fifth go-about, I finally realized I had to walk up the pulpit steps in order see the carvings. So glad I did so, because it is there that I found the object of my search:

No doubt, this was the panel described by Markham as the shield of arms bearing France and England quarterly, surmounted by an imperial crown, and supported on the dexter side by lion rampant quadrant for the Earldom of March, and a bull for Clare; and on the sinister side by a hart, showing the descent from Richard II who took that device, and by a boar for the honour of Windsor possessed by Richard III, the silver boar being his badge.”

I have been researching the use of the boar badge for several months now, and I’ve always been curious about the statement that it was originally from the honour of Windsor. I have yet to locate any confirmed usage of a boar associated with Windsor. Some heraldic experts suggest that the boar was one of the badges of Edward III. Again, I have yet to confirm that. The oldest surviving Garter stall plate at St. George’s, by coincidence, does depict a boar’s head as a crest, but not the full creature.

Also, I think it odd that Markham would conclude the carving dated to the early 1440s under the supervision of the third Duke of York, Richard III’s father. That does not make sense to me since I am not aware of the house of York employing the boar as one of its badges. Yet, it is uncontested that Richard, his son, chose the boar probably when he was in his early teens or pre-teen, and was charged with arraying troops. (Badges were depicted on standards to identify the lord commissioned with the array.) So, the first confirmed Yorkist use of the boar would be somewhere in the mid-1460s, and that coincided exactly with when initial designs for the hearse had been made, in anticipation of the reinterment.

That the boar was designed and made during Edward IV’s reign would lend important information about its iconography. The message conveyed here seems to be that the King announces his descent from the Mortimer line which held the earldom of March and used the cognizance of the white lion. Edward IV is also announcing his claim to be Richard II’s legal heir by depicting that deposed king’s well-known hart cognizance. The black bull of Clarence flanking the dexter side would represent Edward IV’s brother, George, who employed that device as one of his badges. And Edward IV included his youngest brother, Richard, by portraying his badge of the white boar. It’s as though the three sons of York are illuminated here, and they are shown within a unified scheme, with the brothers’ badges being of equal size and support. At the time of the reinterment in 1476, this may have seemed literally true; sadly, only two years would pass, much would change with George’s execution. How times change.

Much to my surprise, I discovered recently that there had been yet another carved boar in the church at Fotheringhay that also dated to the 15th century. The choir that had been built there by the third duke was dismantled and its furniture sold to various purchasers in 1553, during the reign of Edward VI. Some of those choir stalls still exist in the neighboring church of Hemington. According to written accounts, those stalls had misericords depicting a falcon-inside-fetterlock, a rose, a feather issuing from a ducal coronet, a grotesque, and a boar.

Although I wasn’t aware of the Hemington boar when we were at Fotheringhay, I was able to find a photo of the boar on-line:

So, perhaps Markham was right that there was a boar carving in Fotheringhay in the 1440s. And possibly, one could speculate that Richard III as a young lad, might have first set eyes on the boar while he lived there during his first 7-8 years of life, and possibly was impressioned with its symbolism well before he was arraying troops. It would make for an interesting story.

I really enjoyed this, white lily, and think you must be highly chuffed (as the old Brit saying goes) to have found the original boar at Hemington. I for one will have to go there to see it for myself. Thank you for such an informative and colourful post, with great illustrations.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. And I should have credited Princeton University with the photo of the Hemington boar. It has a website devoted to medieval ecclesiastical carvings.

LikeLike

Thank you for posting such an interesting story. Your presentation of your research is so well written.

LikeLike

Thank you, terisoares55.

LikeLike

The ‘feather issuing from a ducal coronet’ will be an Ostrich feather. Contrary to popular belief they were used by all Edward III’s sons, not just the Black Prince.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just re-read this – I don’t understand the Richard II hart reference – it looks to me like a lion and a bull on the central section – and wasn’t Richard II’s hart white? Could the ‘bull’ be a reference to the original Duke of Clarence, rather than Richard II?

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazing article. Can’t wait to see the boar there!

LikeLike